I am delighted to be part of Sean Cunningham’s book tour, in which he will be visiting various blogs and discussing Henry VIII’s elder brother, Prince Arthur, for his new book Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was.

Arthur and Henry: Two Tudor Brothers

Arthur and Henry, the two sons of King Henry VII and Queen Elizabeth, were alive together for only eleven years, between 1491 and 1502. They did not live near each other, and with an age gap of almost five years, could not have had much meaningful interaction until the end of the 1490s at the earliest. Yet the relationship of these two Tudor brothers was one of the most important in English history: not for the time they spent together but for the effect that Prince Arthur’s death had on the destiny of his younger brother Henry.

Arthur was the first Tudor Prince. From September 1486 he was the focus of his father’s hopes and expectations for the future. Arthur’s training was designed to create a king in all-but name. When the moment came for him to take the crown, the prince would have acquired all of the skills, experiences, servants and advisors needed to reign successfully. To reach that point of self-reliance and confidence, Henry VII decided that Arthur must be brought up away from the court and in a region he could come to rule as he grew through his teenage years.

Prince Arthur depicted in mid-Victorian stained glass in St Laurence Church, Ludlow.

Prince Henry’s place during his childhood, in contrast, was in the royal nursery with his sisters Margret, Mary and Elizabeth and brother Edmund; not all of whom survived beyond young childhood. As he got older, Henry received an excellent scholarly education and quickly learned to master the complexity of the court and royal household. Even as a child, he developed his sociability and emphasised his physical good looks. He was ideally suited to a world of display and charm. At his brother’s wedding in November 1501, the ten-year-old Henry drew everyone’s attention when he escorted his future-wife Princess Catherine. He continued to attract the eye during the entertainments when he flamboyantly threw off his very expensive jacket so that he could dance more energetically.

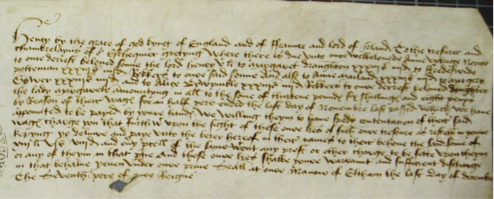

Payments of £13 6s 8d to Anne Uxbridge, nurse to the six-month-old Prince Henry, her team who also looked after Princess Margaret at Eltham Palace, 31 December 1491. In comparison, £46 was paid for the half-year wages of Prince Arthur’s nursery staff at Farnham in June 1487.

Prince Henry showed all the smooth skills of a politician and public figure, but he was not born to be king. For that reason, he was never given the opportunity to learn the weighty responsibilities of ruling, unlike his brother. Henry was about nine years old before we begin to see him learning how the strings of government worked, when he sat-in on sessions of the court of the royal household. By the time Arthur died in April 1502 Henry had barely begun this part of his development.

The training of Arthur and Henry was already so different by the end of the 1490s because Henry VII had already discounted any plan to create geographical power bases for each of his sons. The king might have looked ahead beyond his own death and seen a nightmare vision of his two princes competing as rivals in the same way that George, duke of Clarence and Richard, duke of Gloucester had done in destabilising Edward IV’s reign.

The fleur de Lys badge of Arthur and Henry as princes of Wales, from an Exchequer account of 1508.

That decision meant that Arthur and Henry might have spent very little private time in each other’s company. The brothers would have met at state occasions and probably at other unrecorded times, but their contact can only have been brief. Considering the mass of early Tudor documents that have survived, everyday details of life in the royal household are frustratingly scarce and similar records for Arthur’s life at Ludlow are not yet known.

The former geographical and intellectual distance between the princes heightened the crisis that faced Henry VII by March 1503. The loss of his heir and his wife within a year of each other pushed Henry’s level of confidence and control back to the levels seen in the troubled times of the late 1480s. Conspiracy and rebellion had thrived because the king did not appear consistently strong enough to face threats down. Arthur’s death obliged King Henry to look to his second son as part of a new strategy built around the regime’s survival rather than a thoroughly prepared and unopposed succession. These deaths, and those of other loyal friends in 1503-4, diminished the king’s strength and health too. A sense of rising panic becomes apparent within the Tudor regime, which in turn produced repressive and restrictive policies shaped by those circumstances.

The burial site of Prince Arthur’s heart and other organs in St Laurence Church, Ludlow.

At the age of eleven, Prince Henry was plucked out of his comfortable lifestyle and thrown into the spotlight as the future of everything that his father now hoped to achieve within England. He might have relished the attention but surely found the prolonged effort and expectation difficult to cope with as he became a teenager. By 1503-04, King Henry’s ill health and despondency obliged him to delegate large areas of government control to professional administrators like Edmund Dudley. Prince Henry’s own responsibilities were increasing as he began to take on some of the burden of personal rule that his brother had previously shouldered. The king’s demands for more effort from his son while he, the king, was unable to maintain his former level of involvement in the business of ruling might only have increased the prince’s sense of resentment.

Whether he blamed his brother Arthur for this rapid change in his circumstances cannot be known, but within the year 1502-03 Prince Henry’s life had changed dramatically. If disaster could be avoided for long enough, then Henry knew that he would become king at some point. His learning curve looked daunting. Although it is difficult to see how his former relationship with Arthur worked before that time, it does seem likely that Henry might have identified his brother’s death the origin of a startling transformation in his life.

More importantly, could Henry have blamed Arthur for the death of their mother, Queen Elizabeth? The herald’s account of how the king and queen bore the news of Arthur’s death in April 1502 indicates how Elizabeth tried to reassure her husband with the belief that they could still have more children. Within a few weeks she was pregnant once again. It was the birth of Princess Catherine in February 1503 that caused Elizabeth’s death and left Prince Henry utterly distraught.

A manuscript illustration recently identified in the Vaux Passional (National Library of Wales) shows the court in mourning for the queen with a young prince Henry sobbing in the background. Henry was clearly devoted to his mother. She had died only because Arthur’s fatal illness had forced King Henry and his wife into risking the birth of another child, with the queen aged thirty-seven. Blame would have served no direct purpose but it might have influenced how Henry related to his brother’s legacy more generally thereafter.

The top left of this image from the Vaux Passional (NLW Penarth, 482D, fool. 9), shows a sobbing Prince Henry near his sisters mourning the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1503.

Henry VIII carried plenty of other emotional baggage as a result of his brother’s early demise. The age of eleven is a crucial time in any child’s life and severe emotional stress at that point can have unexpected and long-term effects. Trying to spot those with certainty in someone alive five hundred years ago is difficult and unwise, but it can be an interesting way of looking for patterns of evidence that allow us to think differently about what we know already.

Can we see the origins of Henry VIII’s adult personality in the events that emerged from the circumstances of Prince Arthur’s death? That might be taking the connection too far; but there clearly was a link between what happened in 1502-03 and the big changes that then occurred to the trajectory that Prince Henry’s life was on.

Unsurprisingly, Henry developed a lifelong mortal fear of infectious disease. Before he was ten years old, Prince Henry had seen his brother Edmund and sister Elizabeth die in the palace where he lived. By the time he was twelve, Henry was also without his mother and Prince Arthur. It is often easy to dismiss the impact that death had upon late medieval lives, since its presence was constant. Henry VIII’s anxiety over his vulnerability, however, seems almost obsessive until he was in his mid-forties and Prince Edward had been born (in October 1537).

The strength of that fear suggests a childhood origin that was later heightened by recurring outbreaks of disease. Some of that feeling of dread came from personal experience after 1509, but it might also have emerged from Catherine of Aragon’s intimate knowledge of the epidemic that struck down Prince Arthur in 1502. The longer Henry VIII reigned without a male heir, the more magnified this fear of sudden death became. His apprehension stood in contrast to the direct risks of violent injury on the tiltyard that Henry was happy to ignore.

In itself this contrast illustrates something about Henry VIII’s complex personality: he could project to the public a fearless and powerful impression of martial kingship at the same time as he held private terrors that were almost paralysing. That inner conflict progressed inexorably to the point that he was willing to contemplate the most massive changes to England’s social structure and political/religious status around Europe in order to reset his life on his own terms. Whereas providence had caused Henry’s life to alter after 1502, by the spring of 1527 he was willing to change everything else around him within the polity in order to marry again and produce a male heir who would secure the continuation of Tudor power as he required.

Henry VIII in later life from the Plea Roll of King’s Bench.

When he was young, Henry had tried to deal with his status as a second-son through the cultivation and projection of a beaming personality. Henry got on well by working out how to deal with people directly. Arthur must have had many of those skills too, but he was also expected to know how to rule through institutions, processes and mechanisms. Henry’s focus on the gloss and not the substance of kingship led him to delegate easily. Here he took the lead from Henry VII’s promotion of Edmund Dudley after 1504. Henry’s unwillingness to engage with the detail of government allowed Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell to develop Tudor bureaucracy to even greater heights than were likely under King Arthur. So one of the benefits of Henry VIII’s ruling style was the quicker emergence of the smooth-running Tudor civil service.

Henry seems to have loved his brother deeply, but more as an ideal image of princely virtue than as an elder sibling with whom he had shared childhood rough-and-tumble. Their separate households must have prevented regular contact of that type. Henry kept some of Arthur’s clothes. He acquired Arthur’s books, like the copy of Cicero’s De Officiis (On Duties) that Henry added his name to. Arthur’s portrait and altered copies of it were in the royal collection during Henry’s reign. There is enough evidence that Arthur was regularly in Henry’s thoughts long before the details of his brother’s sexual relationship with Catherine of Aragon commanded the king’s full attention at the end of the 1520s.

It seems that Arthur was a constant point of reference for Henry’s adult life. Henry had followed in Arthur’s footsteps as second son, second Prince of Wales, and second husband to Catherine of Aragon. Arthur probably remained mysterious and distant to his brother. Henry may have learned more about his brother’s character through second-hand conversations after 1509 with Queen Catherine and others who had known Arthur at Ludlow, than he drew from his own memories. If this had led to Henry developing a sense of personal inferiority to Arthur it was soon overturned by the momentous and bold decisions made by the king in the 1530s. Throughout his reign until his own Prince of Wales was born, Henry VIII might have had a constant need to relate his own capacity as king to the achievements denied to Arthur by his premature death. We remember Henry because he lived to reign and change Britain’s national identity. Henry probably remembered Arthur because, by the 1540s, he had proved that he could rule in a way that Arthur might have recognised and been proud of.

Bio:

Dr Sean Cunningham, is Head of Medieval Records at the UK National Archives. He main interest is in British history in the period c.1450-1558. Sean has published many studies of politics, society and warfare, especially in the early Tudor period, including Henry VII in the Routledge Historical Biographies series and his new book, Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was, for Amberley. Sean is about to start researching the private spending accounts of the royal chamber under Henry VII and Henry VIII for a new project with Winchester and Sheffield Universities. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and co-convenor of the Late Medieval Seminar at London’s Institute of Historical Research.

Book available from Amberley, Amazon and other online outlets and bookshops.

Pingback: Prince Arthur: The Tudor King Who Never Was – Book Review | Through the Eyes of Anne Boleyn