I am delighted to be part of Olivia Longueville’s book tour, in which she will be visiting various blogs and discussing Anne Boleyn for her new book Between Two Kings. For your chance to win a paperback copy of her book, simply leave a comment after this post between now and 16th January 2016. The giveaway is open internationally and don’t forget to leave your name and a contact email. A winner will randomly be selected and contacted by email shortly after the competition closes.

Blurb:

Anne Boleyn is accused of adultery and imprisoned in the Tower. The very next day she is due to be executed at the hand of a swordsman. Nothing can change the tragic outcome. England will have a new queen before the month is out. And yet…

What if events conspired against Henry VIII and his plans to take a new wife? What if there were things that even Thomas Cromwell couldn’t control, things which would make it impossible for history to go to plan?

The year is 1536.

History is about to be changed forever.

The old Anne Boleyn is dead.

The new Anne is a cold and calculating woman.

Between Two Kings.

About the author:

Olivia Longueville, author of Between Two Kings, has degrees in finance and general management from London Business School and currently helps her father run the family business.

Olivia loves historical fiction and is passionate about historical research, genealogy, and art. She has undertaken in-depth research into the history of the Valois dynasty, the French Renaissance and the Tudors and Plantagenets.

As an amateur historian, Olivia has chosen to explore her interests through fiction. Her most cherished dream has always been to re-imagine Anne Boleyn’s life, leading her to recreate the story of Anne with a twist – Anne taking revenge against those who wronged her and caused her downfall.

The Doomed Romance of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII

Passion. Promises. Marriage. Betrayal. Heartbreak. Murder. A doomed romance that has captivated historians and everyday people across centuries and around the globe. The tragic story of Anne Boleyn and her romance with King Henry VIII continue to fascinate and shock us today, nearly five hundred years later.

Perhaps if Anne had lived a full life and had a happy marriage with Henry, her story wouldn’t have been so utterly captivating, and it wouldn’t have fascinated so many generations with its tremendous intensity and vehement passion, its unparalleled challenge to the conventional traditions of Tudor England, and its gruesome and unfair end that to us appears inevitable but shocking nevertheless.

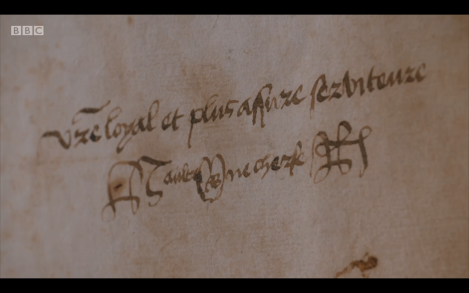

In the brightest hours of Anne’s youth, when she had just returned from France and was shining like a diamond in the splendour of the English court, Henry met her at the Château Vert pageant.

A lovely young lady curtsies. A handsome, virile king briefly acknowledges her. A small and seemingly meaningless moment, like so many others, as the powerful Henry surely met many young women at such pageants. Yet, it was this meeting which altered English history forever. Apparently, several years passed before Henry took a serious interest in Anne and began his pursuit of her, at first thinking that she would be just another amorous conquest, and he would be able to charm her with rich and extravagant gifts.

I’ve never believed that Anne was so ambitious and avaricious that she played a crafty and guileful game of an unavailable, virtuous young woman, trying to entice and seduce Henry into leaving Catherine of Aragon. There is no evidence that she was a great mastermind who planned on attempting to usurp the crown from the outset; contemporary sources also suggest that her father, Thomas Boleyn, and her uncle, Thomas Howard, were not very keen on her marriage to the king.

Instead, Anne left the court in 1527, when Henry’s unwavering interest in her might have tarnished, if not ruined, her reputation. She didn’t forget that her elder sister, Mary Boleyn, had once been a royal mistress, who had been discarded and evicted from the Boleyn family, and she didn’t want to follow Mary’s path.

Anne wasn’t going to surrender her virtue to the king, and Henry wasn’t going to stop hunting her. He desperately coveted Anne; a stirring of madness took over the king who was burning with desire, suffering from unrequited love, and was distraught that she was refusing him again and again. I think that Anne was charmed by Henry, flattered by his attentions to her humble persona, and awed by his insistence, which was slowly pushing her to the threshold of surrender. Passion flared between the two, bright and hot like a freshly lit torch, and eventually they succumbed to their desires and began a romantic relationship.

We often ask ourselves whether Anne and Henry could have had a happy ending. I think that the answer is a , not only because Anne failed to birth a healthy son, but also because Henry wasn’t capable of making any woman happy.

When Anne decided to begin her quest for queenship, which, in my opinion, happened after Henry’s proposal to marry her, she predestined her own greatness – to become one of the most tragic queens who ever lived. A queen who changed the course of history and gave birth to one of the greatest monarchs to ever sit on the throne of England – Elizabeth I. However, her choice doomed her to a terrible, early death, although she couldn’t know about that.

In his youth, Henry was a glorious Tudor prince who married Catherine, the widow of his elder brother. Henry was so devoted to Catherine that he jousted in her honour as “Sir Loyal Heart” and laid trophies at her feet at tournaments. Years were passing, and Catherine was pregnant many times, but she failed to produce a male heir. Henry’s eye began to wander towards young maidens, and when Elizabeth Blount, one of his mistresses, gave him a son, he became assured that he was capable of fathering healthy sons, blaming Catherine for her failure to bear a son.

After meeting Anne, Henry became enamoured of her and resolved to have his marriage to Catherine annulled, stating that his ageing and barren wife had never been truly married to him because she was his brother’s widow.

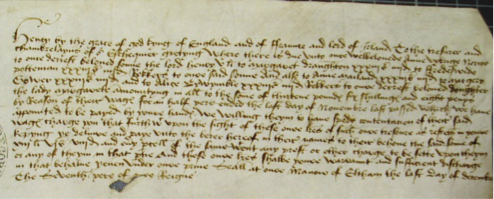

To vindicate his opinion about the invalidity of his first marriage, he referred to the passage in chapter 20 of the Book of Leviticus: “And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.” [Leviticus 20: 21] Anne and Henry were in love and wanted to marry, but Catherine stood in the way of their plans for a long time as the Great Matter (the efforts to secure a divorce from Catherine) dragged on and on. In the end, the king broke from Rome and married Anne.

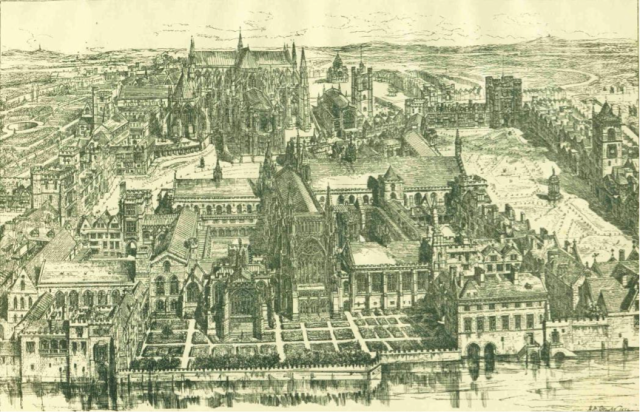

When he was proclaimed Supreme Head of the Church of England, Henry became the most powerful man in England, as his authority extended beyond the political realm and into the spiritual. A tapestry of his future with Anne emerged in the brightest colours as he hoped to have his Tudor prince soon.

He was still enamoured with Anne, but, strictly speaking, his love for her wasn’t a pure, unselfish feeling – it was conditional upon Anne’s promise to give him a son. In some ways, Henry’s relationship with Anne might be considered a bargain: he craved to make Anne belong to him both carnally and legally as his queen, because he “loved” her and because she probably promised him a son, and if she fell short of his expectation, she had to suffer the consequences.

Anne gave birth to Elizabeth in September 1533, which disappointed Henry a lot, but it seems that he still hoped they were young enough and would have sons later. But fate had different plans for the royal couple: Anne suffered several miscarriages, Henry renewed the practice of keeping mistresses, and soon he began to lust for Jane Seymour.

The ageing king’s obsession with sons predetermined that Anne wouldn’t be given as much time as Catherine. The longer the Great Matter dragged on, the more frustrated he was becoming and the higher his expectations of Anne became. When he married her, he was already running out of patience. Anne tried hard to fulfil her promise, and she was pregnant at least three times (including Elizabeth), if not more, but she still failed to produce a living son.

Henry was losing hope that Anne would produce a son. The king wasn’t the same man who had once fallen for young Anne: he had become a callous, hedonistic, and egotistical monarch, who tasted absolute power and who began to consider himself God’s incarnation on earth. The worst aspect of this situation was that Anne herself helped him obtain this absolute power, which eventually destroyed any chance that she may have had to sustain her marriage until a son could be born and to live out her natural lifespan.

Anne’s final miscarriage, which she suffered in January 1536, led to Henry’s irrevocable disenchantment with their marriage. In retrospect, he was embarrassed over the turmoil he had caused in England in his quest to marry her. He began to believe that his second marriage hadn’t been blessed by God. Henry wanted Jane as his wife, and, probably, he had already entertained thoughts of ending his marriage to Anne.

At this point, everything went downhill for Anne: seizing their chance, Anne’s enemies conspired against her and orchestrated her downfall, maybe at Henry’s own order, and she was executed.

In my opinion, Henry was a narcissistic and selfish man. In mythology, Aphrodite was appalled by Narcissus’ rude behaviour, and she cursed him as a punishment, making him fall in love with himself. Narcissus was doomed to spend eternity sitting at the edge of a pond, contemplating his own reflection in the water in dazed fascination.

I wonder who placed a curse of narcissism on Henry? As a favourite of Elizabeth of York and Margaret Beaufort among Henry VII’s children, he received much fawning attention as a boy and young man. However, as a second son, he was originally the “spare heir,” so perhaps his narcissism was an inborn trait. At the height of his power, Henry became a malignant narcissist who assumed a God-like status in England.

Truth be told, I cannot see Henry happy with Anne or any of his other five wives. Although in his youth, he seems to have loved Catherine genuinely. I don’t think that Anne would have been happy with the king in the long term even if she had remained Queen of England and succeeded in placing a healthy Tudor prince in the royal cradle.

Henry’s feelings for his wives are more accurately described as lust, not love. The king loved too many women and his love always faded like a rainbow after a storm, like a word whispered into darkness, if their “love” failed him by not giving him the heir that he desired above all else.

What would have happened if Anne had given Henry a son before May 1536? Henry would have had to keep her as his wife, but he wouldn’t have been a caring and faithful husband to her. He had been engaged in extramarital affairs before her final miscarriage, and he wouldn’t have changed his behaviour.

In Henry’s view, God had ordained him to be King of England and Head of the Church of England, and he was subject only to God’s judgement. Over the course of time, Anne would have aged, and Henry would have wanted younger lovers: his eye would have strayed from her more and more often, focusing instead on the seemingly endless supply of exquisite belles who were paraded before him, flaunting their youth and beauty and wrapped in silks and fineries.

Most likely, Anne would have eventually learnt a lesson and turned a blind eye to Henry’s amorous escapades, just as Catherine had throughout the many years of her marriage to Henry.

Anne would have watched her husband’s betrayals with her head held high, plastering a fake smile on her face. Her resentment towards the king would have been growing, and she would have begun to question closely, in her own heart, the shadowy motive that lay behind the lack of her affection for him. She would have laughed and smiled in public, but she would have been dreaming of a happier life. Eventually, Anne’s heart would have stopped lighting with fires of emotion and passion when Henry lavished her with affections and came to her bed, and she would have fallen out of love with him.

If Anne and Henry had only one son, the probability that he might have died in childhood was high because the child mortality rate was high in the Middle Ages and in the Tudor period. If Anne’s son had died, Henry would have turned berserk with rage and would have blamed her for the tragedy: he always put the blame for his misfortunes and afflictions on others, as his self-enamoured and vainglorious nature prevented him from blaming himself. Anne would have lost Henry’s favour, and he would have started hating her and would have eventually gotten rid of her.

Regardless of her ability to bear a son, Anne would have been miserable with Henry. She was doomed to sustain many heavy afflictions with fortitude in her marriage even if she had survived. The romance of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII was tragic and doomed from the beginning.

The king’s chronic inability to make Anne happy pushed me to invent an alternative scenario where Anne survives, is no longer married to Henry, takes revenge against those who brought her down, and finds her happiness with another powerful king – King François I of France. That’s the premise behind my new novel, Between Two Kings.

I write poetry when I want to convey a wealth of emotions that cannot be easily relayed in even my lyrical prose. This poem is about Anne’s doomed love for Henry VIII.

Doomed Love

I, the innocent Queen, sit alone in the Tower,

Death waits for me at the foot of the Tower.

I hear the cannon, be silent, I pray,

Otherwise I would feel much more betrayed.

Oh, Henry! Your love for me was fake and doomed.

You fell in love with me, but love soon perished.

I never thought you would break my heart,

I guess I should never believe you from the start.

You were my world, my Henry, my beloved,

You were my present and my past, my life.

The future seemed a marvel and delight,

But your betrayal did lay siege to our love.

You talked about love with that look in your eye,

And that was all a stupid, empty lie,

Because you can love nobody but yourself,

A bleeding heart you gave me, not yourself.

Tears of blood are falling from my heart.

I have been wretched and condemned by your love.

That doomed love had broken me and my friends.

That love had stripped me of all my dreams.

Had I never loved you deeply and madly,

Had I never trusted your promises blindly,

Never met and never fell in love with you myself,

I would have never doomed myself to death.

You made me tremble and swoon in shiver,

You sent me, innocent, to shameful death.

You, mad from your obsession for a male heir,

Deprived me of my sleep and left me only breath.

At the Tower window, I sit and wait for death,

Delighted that French steel, not English axe,

Is doomed to take my life and breath,

As a final act of your fake mercy to me.

Sweet and cherished death, I feel you in the air,

But all my pain is gone, and I feel no despair.

I look into the sky and see the sun, the light of Heaven.

Death is not scary at all – it is oblivion.

I feel tears fall down, and I whisper good-bye,

Glad to death’s mystery and to be gone from this life.

Words spoken and wasted, hearts broken, love gone,

But you will remember me long after I am gone.

Henry is soon married to Katherine Howard, a 15 year old in this series, although Worsley does say we do not know for certain how old she was, just that she was the youngest of his wives and a teenager (not that they thought of them as teenagers back then, they were adults). Worsley does seem to contradict herself with Katherine, stating that she believes she was a victim of child abuse, which I personally am inclined to believe with Mannox and Dereham but not with Culpepper. Katherine’s guardian, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, should have protected her from her music teacher and then the likes of Dereham. Worsley states how Katherine could just be telling Culpepper what he wanted to hear in her letter to him, yet the scene with Katherine and Culpepper clearly show that Katherine was in love with him. She backs this up by saying that Culpepper raped a farmer’s wife and only got let off because he was one of Henry’s favourites, which is true, but this very easily could have been more like a crush on Katherine’s part, even perhaps starting before her marriage to the king. What Worsleg says and what the drama shows doesn’t quite add up.

Henry is soon married to Katherine Howard, a 15 year old in this series, although Worsley does say we do not know for certain how old she was, just that she was the youngest of his wives and a teenager (not that they thought of them as teenagers back then, they were adults). Worsley does seem to contradict herself with Katherine, stating that she believes she was a victim of child abuse, which I personally am inclined to believe with Mannox and Dereham but not with Culpepper. Katherine’s guardian, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, should have protected her from her music teacher and then the likes of Dereham. Worsley states how Katherine could just be telling Culpepper what he wanted to hear in her letter to him, yet the scene with Katherine and Culpepper clearly show that Katherine was in love with him. She backs this up by saying that Culpepper raped a farmer’s wife and only got let off because he was one of Henry’s favourites, which is true, but this very easily could have been more like a crush on Katherine’s part, even perhaps starting before her marriage to the king. What Worsleg says and what the drama shows doesn’t quite add up.